Jesus and the Roman Empire

Summary

Why Understanding the 1st Century Dynamics between the Roman Empire and Jews is Important to Forming a New Image of Jesus

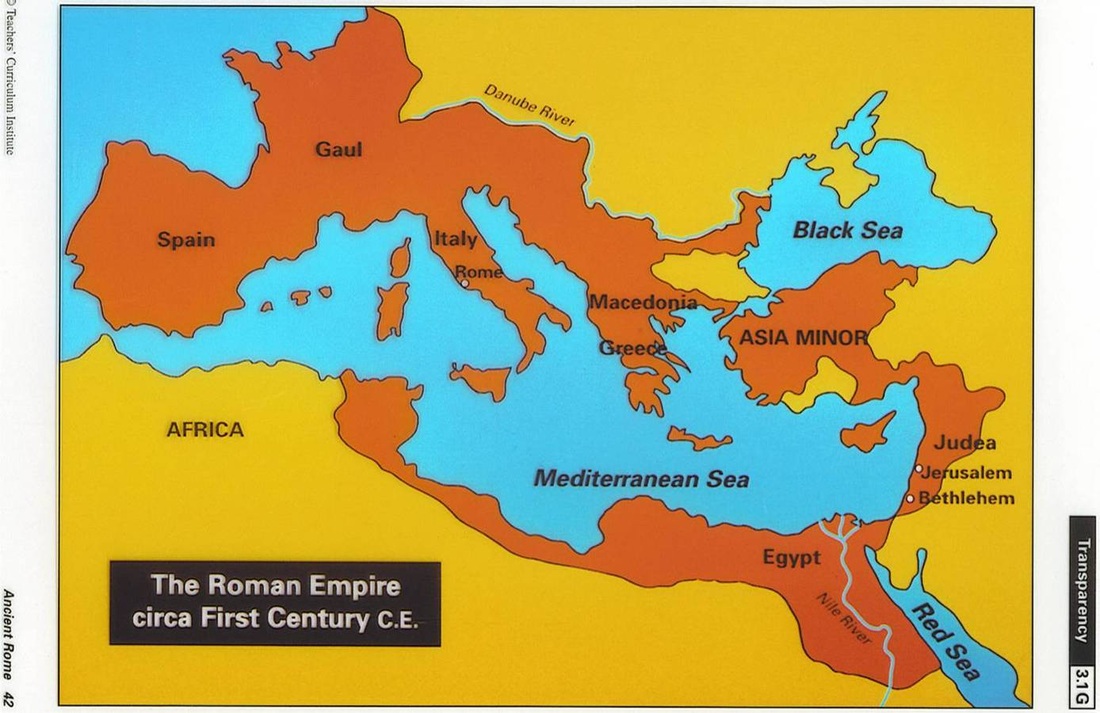

Western Christianity has domesticated and “depoliticized” Jesus (Horsley 2003, 6). As we have domesticated Jesus, we have so domesticated his background. We talk about “Jews” as if they are a single entity, but in fact the society Jesus lived in was very complex and involving many realities that influenced his teachings. “The peoples of Palestine in the time of Jesus appear as a complex society full of political conflict rather than unitary religion (Judaism) (Horsley 2003, 10).” Opposition to Roman injustice and rule regularly marked the immediate Palestinian context of Jesus’ ministry. Horsley asserts one cannot comprehend Jesus in isolation but with the historical conditions surrounded around Him (Horsley 2008, 18). He cites the cultural traditions, Jewish roots, and predicaments of Jewish and Galilean people in the 1st century to Jesus’ leadership and overall ministry (Horsley 2008, 18).

Therefore, “trying to understand Jesus’ speech and action without knowing how Roman imperialism determined the conditions of life in Galilee and Jerusalem” is rather like “trying to understand Martin Luther King without knowing how slavery, reconstruction, and segregation determined the lives of African-Americans in the United States (Horsley 2003, 13).” Horsley wants us to read Jesus as a leader who “belonged in the same context with and stands shoulder to shoulder with these other leaders of movements among the Galilean and Judean people, and pursues the same general agenda in parallel paths”: independence from Roman imperial rule and a restored rule of God (Horsley 2003, 104).

Biblical scholar Christopher Bryan questions “How far should these considerations (Roman imperialism and Jewish experience under that rule) affect our understanding of Jesus of Nazareth (Bryan 2005, 7)?” This question is the basis of my study. I wanted to explore the political readings of Jesus in the Gospels using the techniques of postcolonial biblical criticism. Most scholars that I read agreed that Jesus according to the Gospels was political or revolutionary. In the next section, I will explore some scholars’ assertions of Jesus’ words and deeds that can be determined in through a postcolonial biblical critic lens as political.

The Words and Deeds of Jesus

In recent years there has been a surging assertion that the gospel of Mark can be read as a “political” interpretation of Jesus (Moore 2006, 194). Reading Mark with a zealot lens and historical context of the time period positions Mark as “anti-imperial literature, pure and simple” (Moore 2006, 196). Tat-sioing Benny Liew like Stephen D. Moore understands that “most scholars who read Mark’s Gospel in light of Roman colonization of Palestine in the first century CE have interpreted the Gospel as a document for liberation (Liew 2006, 206).” Liew concludes that although Mark may critique the current colonial order, it also “reinscribe(s) colonial domination.” Liew claims that Mark’s Jesus “has absolute authority in interpreting and arbitrating God’s will.” Marks’ politics of parousia remains “a politics of power, because Mark still understands authority as the ability to have one’s commands obeyed and followed, or the power to wipe out those who do not.” Liew declares Mark’s Gospel has a recurring theme of “empire” in the form of “tyranny, boundary, and might (Liew 2006, 215-216).”

Mark’s representation of empire in his gospel raises the question if Mark is merely mirroring Roman imperial ideology and switching Jesus with Caesar (Moore 2006, 200). Moore sees Mark 5:1-9 as a dual reference to demonic possession and colonial occupation. Demons perhaps like the Romans are occupying the Jew’s property, so Jesus’ exorcism represents liberation from this authority and unwanted invasion (Moore 2006, 194). Mark is not overly political or critical of the Roman Empire compared to Revelation, but nonetheless there are still significant trickles of allegations against Rome and want for freedom from them (Moore 2006, 201).

Adam Gopnik like many other Jesus scholars states that, “If Jesus says something nice, then someone is probably saying it for him; if he says something nasty, then probably he really did (Gopnik 2010, 2).” Gopnik claims two particular instances where Jesus gets “nasty’ with the not only the Romans of the day but the Jews too. One instance was Jesus’ rules for eating. Jesus breaks Roman and Jewish norms by eating with prostitutes and tax collectors (Gopnik 2010, 5). Gopnik reads the scene in Mark 12:17 as another attempt by the high priests to catch Jesus in a declaration of anti-Roman sentiment. Jesus’ response is brilliant in Gopnik’s mind because Jesus turns the question back on the questioner in mock-innocence. Gopnik calls it a “tautology designed to evade self-incrimination (Gopnik 2010, 4).”

Bruce N. Fisk in his new book through the character of Norm, a recent religion graduate, illustrates a journey to discover the Jesus of History and the Jesus of Gospels. Norm like his past professors of biblical criticism is not convinced that every Bible story can be “taken at face value”, so he decides to find out who Jesus is (Fisk 2011, 15). One of the many topics Norm touches on in chapter 6 that I never realized until reading this book was the political overtones of Jesus. I always saw Jesus as a spiritual leader not a political one. When Norm mentions how the parade on the donkey could have been a parody of Pilate’s military parade and a challenge to Roman rule, this challenged my ideology of Jesus (Fisk 2011, 195). Warren Carter seconds this claim of Jesus as a political leader. Carter concludes that Romans do not crucify people because they are spiritual; they crucify people because they seem them as a political threat to the Roman system (Carter 2006, x).

This notion of Jesus as a political leader rather than a spiritual leader can be interpreted using the Gospel of John. Stephen D. Moore contends that John is “the most-and the least-political of the canonical gospels.” He gives support for the most political gospel as John’s clear word choice in John 6:15, 12:12, 11:48, and 19.7 (Moore 2006, 50). John “represents the charges brought against Jesus as political charges with a consistency and single-mindedness that is altogether absent from the Synoptic tradition (Moore 2006, 50-51).” Moore stresses that John is on other the hand the least political of the canonical gospels it that John’s same passion narrative “seems to place Jesus’ kingship front and center only in order to depoliticize it (Moore 2006, 50-51).”

The Legacy of Jesus through Paul’s Letters

Paul’s gospel of Christ announced “doom and destruction not on Judaism or the Law, but on the rulers of this age (Horsley 1997, 6).” Horsley suggests given the historical context of Paul’s mission that it is not difficult to draw the implications of Paul’s opposition to the Roman Empire. Horsley cites Romans 9-11 and Galatians 3 where Paul asserts in those letters history has not been primarily working through Rome but through Israel. Paul asserts fulfillment of history has now come with Jesus (Horsley 1997, 7). Unlike the other sources, this book looks at the relations between the Jews turned Christians and Romans after Jesus’ death. Looking at Paul’s mission and language, Horsley explores the legacy of Jesus’ political implications in the mid 1st century. Horsley suggests that by looking at Galatians and Corinthians, one can understand the sense of the commission that Christ had given Paul to build not religious in the sense of Roman context communities but local and politically charged Christians ready for “the kingdom of God” and promises of Jesus (Horsley 1997, 8).

Western Christianity has domesticated and “depoliticized” Jesus (Horsley 2003, 6). As we have domesticated Jesus, we have so domesticated his background. We talk about “Jews” as if they are a single entity, but in fact the society Jesus lived in was very complex and involving many realities that influenced his teachings. “The peoples of Palestine in the time of Jesus appear as a complex society full of political conflict rather than unitary religion (Judaism) (Horsley 2003, 10).” Opposition to Roman injustice and rule regularly marked the immediate Palestinian context of Jesus’ ministry. Horsley asserts one cannot comprehend Jesus in isolation but with the historical conditions surrounded around Him (Horsley 2008, 18). He cites the cultural traditions, Jewish roots, and predicaments of Jewish and Galilean people in the 1st century to Jesus’ leadership and overall ministry (Horsley 2008, 18).

Therefore, “trying to understand Jesus’ speech and action without knowing how Roman imperialism determined the conditions of life in Galilee and Jerusalem” is rather like “trying to understand Martin Luther King without knowing how slavery, reconstruction, and segregation determined the lives of African-Americans in the United States (Horsley 2003, 13).” Horsley wants us to read Jesus as a leader who “belonged in the same context with and stands shoulder to shoulder with these other leaders of movements among the Galilean and Judean people, and pursues the same general agenda in parallel paths”: independence from Roman imperial rule and a restored rule of God (Horsley 2003, 104).

Biblical scholar Christopher Bryan questions “How far should these considerations (Roman imperialism and Jewish experience under that rule) affect our understanding of Jesus of Nazareth (Bryan 2005, 7)?” This question is the basis of my study. I wanted to explore the political readings of Jesus in the Gospels using the techniques of postcolonial biblical criticism. Most scholars that I read agreed that Jesus according to the Gospels was political or revolutionary. In the next section, I will explore some scholars’ assertions of Jesus’ words and deeds that can be determined in through a postcolonial biblical critic lens as political.

The Words and Deeds of Jesus

In recent years there has been a surging assertion that the gospel of Mark can be read as a “political” interpretation of Jesus (Moore 2006, 194). Reading Mark with a zealot lens and historical context of the time period positions Mark as “anti-imperial literature, pure and simple” (Moore 2006, 196). Tat-sioing Benny Liew like Stephen D. Moore understands that “most scholars who read Mark’s Gospel in light of Roman colonization of Palestine in the first century CE have interpreted the Gospel as a document for liberation (Liew 2006, 206).” Liew concludes that although Mark may critique the current colonial order, it also “reinscribe(s) colonial domination.” Liew claims that Mark’s Jesus “has absolute authority in interpreting and arbitrating God’s will.” Marks’ politics of parousia remains “a politics of power, because Mark still understands authority as the ability to have one’s commands obeyed and followed, or the power to wipe out those who do not.” Liew declares Mark’s Gospel has a recurring theme of “empire” in the form of “tyranny, boundary, and might (Liew 2006, 215-216).”

Mark’s representation of empire in his gospel raises the question if Mark is merely mirroring Roman imperial ideology and switching Jesus with Caesar (Moore 2006, 200). Moore sees Mark 5:1-9 as a dual reference to demonic possession and colonial occupation. Demons perhaps like the Romans are occupying the Jew’s property, so Jesus’ exorcism represents liberation from this authority and unwanted invasion (Moore 2006, 194). Mark is not overly political or critical of the Roman Empire compared to Revelation, but nonetheless there are still significant trickles of allegations against Rome and want for freedom from them (Moore 2006, 201).

Adam Gopnik like many other Jesus scholars states that, “If Jesus says something nice, then someone is probably saying it for him; if he says something nasty, then probably he really did (Gopnik 2010, 2).” Gopnik claims two particular instances where Jesus gets “nasty’ with the not only the Romans of the day but the Jews too. One instance was Jesus’ rules for eating. Jesus breaks Roman and Jewish norms by eating with prostitutes and tax collectors (Gopnik 2010, 5). Gopnik reads the scene in Mark 12:17 as another attempt by the high priests to catch Jesus in a declaration of anti-Roman sentiment. Jesus’ response is brilliant in Gopnik’s mind because Jesus turns the question back on the questioner in mock-innocence. Gopnik calls it a “tautology designed to evade self-incrimination (Gopnik 2010, 4).”

Bruce N. Fisk in his new book through the character of Norm, a recent religion graduate, illustrates a journey to discover the Jesus of History and the Jesus of Gospels. Norm like his past professors of biblical criticism is not convinced that every Bible story can be “taken at face value”, so he decides to find out who Jesus is (Fisk 2011, 15). One of the many topics Norm touches on in chapter 6 that I never realized until reading this book was the political overtones of Jesus. I always saw Jesus as a spiritual leader not a political one. When Norm mentions how the parade on the donkey could have been a parody of Pilate’s military parade and a challenge to Roman rule, this challenged my ideology of Jesus (Fisk 2011, 195). Warren Carter seconds this claim of Jesus as a political leader. Carter concludes that Romans do not crucify people because they are spiritual; they crucify people because they seem them as a political threat to the Roman system (Carter 2006, x).

This notion of Jesus as a political leader rather than a spiritual leader can be interpreted using the Gospel of John. Stephen D. Moore contends that John is “the most-and the least-political of the canonical gospels.” He gives support for the most political gospel as John’s clear word choice in John 6:15, 12:12, 11:48, and 19.7 (Moore 2006, 50). John “represents the charges brought against Jesus as political charges with a consistency and single-mindedness that is altogether absent from the Synoptic tradition (Moore 2006, 50-51).” Moore stresses that John is on other the hand the least political of the canonical gospels it that John’s same passion narrative “seems to place Jesus’ kingship front and center only in order to depoliticize it (Moore 2006, 50-51).”

The Legacy of Jesus through Paul’s Letters

Paul’s gospel of Christ announced “doom and destruction not on Judaism or the Law, but on the rulers of this age (Horsley 1997, 6).” Horsley suggests given the historical context of Paul’s mission that it is not difficult to draw the implications of Paul’s opposition to the Roman Empire. Horsley cites Romans 9-11 and Galatians 3 where Paul asserts in those letters history has not been primarily working through Rome but through Israel. Paul asserts fulfillment of history has now come with Jesus (Horsley 1997, 7). Unlike the other sources, this book looks at the relations between the Jews turned Christians and Romans after Jesus’ death. Looking at Paul’s mission and language, Horsley explores the legacy of Jesus’ political implications in the mid 1st century. Horsley suggests that by looking at Galatians and Corinthians, one can understand the sense of the commission that Christ had given Paul to build not religious in the sense of Roman context communities but local and politically charged Christians ready for “the kingdom of God” and promises of Jesus (Horsley 1997, 8).